Reading Rebellious Nature and Anti-Christian Sentiments in Japanese Video Game Character Design

Andreas J. Pratama

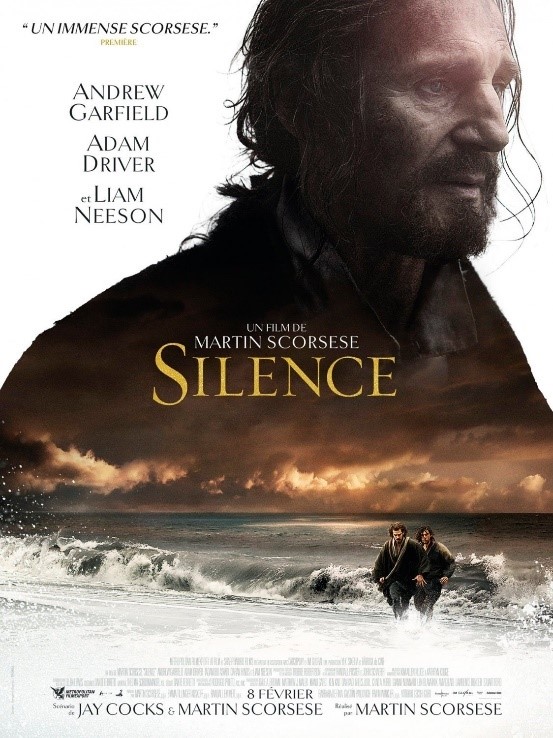

It was no doubt that Japan had a tumultuous relationship with the West back in 1400s until the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s. The Tokugawa shogunate was quite contradictory to the Christian teaching and prefer instead of close themselves off to the world rather than being openly inclusive of the Western influences and trades. Portrayed in the movie “The Silence” (2016) the Christian priests and preachers who travelled to japan were being stripped of their belief and confined within their own religious standards which leads to the moment where their faith is personally questioned.

The questioning of faith has always been a part of our everyday lives. The reality often confronts us and presented us with doubts, technology constantly provides critical perspectives in which nearly everything religious is under the hammering questions. Borrowing from characters that questions the morality of the Church CAPCOM’s Devil May Cry has always been contextually challenges the notion of good vs evil narrative in their character ideology. Dante, after Dante Alighieri of the Renaissance Italy, was a character that went on a harrowing journey with his guide the poet Virgil. In the Devil May Cry franchise such names were borrowed only to the extent of providing co-text and comparison to the rebellious nature of the duo. In the latest franchise Devil May Cry 4 and 5 the iteration saw the addition of Nero, a yet another rebellious youth, that borrows the name from Roman Emperor’s most notorious killer of early Christians. These were some examples of how the name – borrowing and context infused narrative were positioned in the Devil May Cry Franchise.

Transfigured ‘Credo’ from DmC4

“Acceptance” from Bayonetta

The monster designs of Devil May Cry 4 and Bayonetta are similarly identical, in which most of the monstrous figure portrayal appearing as opponents are none other than the strangely church-like baroque adorned angelic-monster hybrid. The game themselves were never blatantly and openly vocal about its anti-church or anti-Christian mentality, but rather a build up of subconscious narrative built upon by history, local beliefs, otherings, and Japanese modernity construct. Japan was already inclusive of Christianity ever since they open themselves up to the West in the 19th century, but the comfort zone in which they are free to question and suspect is always open to possibilities.

Portrayal of Fortinbras

In Shin Onimusha: Dawn of Dreams, the last boss was called “Fortinbras” a Western looking gentleman of royalty appearing out of nowhere challenging Hideyasu Yuki, illustrating himself as the God of Light. Perhaps a lamentation to the field of industrialization in which timelessness of pace of life became inherently changed forever, this depiction appears to hint at the identity conflict between the two further romanticizing the classic Japanese romanticism and the erosive modernism that the west brings. Some of the more widely accepted adaptation to the horrors that Japan had previously experienced also took form in Gigantic battles commonly seen in Ultraman and Godzilla. Godzilla as a mutant was a byproduct of nuclear accident comparable to the horror of Hiroshima atomic incident. Eradication on such a gigantic scale is capable of destruction by an equally gigantic monster as well.

Comments :