Reacting to ‘Sexy Killers’ the Documentary

Andreas J. Pratama

Humans are visual creatures, and by such ideal, anyone born not devoid of their visual perception will put to use this biological feature instinctively and naturally. Such innate feature is often taken for granted, with unpolished knowledge and the alarming rate in which instant culture sprawls today renders our thinking-feeling capability disarmed. The recent viral shares of the documentary ‘Sexy Killers’ (2019) released just weeks prior to the Indonesian national election is muddled with hundreds if not thousands of different public thoughts anything from both rejecting and accepting its validity as a documentary. My very own personal view on the documentary does not matter, although it cannot be separated entirely from influencing this written article: my sympathy for the failures of many to get what the documentary is striving to argue. However, there is one particular thing I would like to underline here: Beyond the sexy, sappy, emotionally charged anger and sadness or political sentiments that has been dauntingly dragging for so long between both the Jokowi and Prabowo sides are soiling the main argument of the documentary itself. Yes, I am aware that the motive can be read as anarchistic, promoting apathy (GOLPUT) towards the election, anyone worth their grains of salt will know that politics are never black and white / good – evil / pure – impure some good are necessary evil and some evil are necessary good. But all of these are fallouts and misinterpretations from the main target in which the documentary is targeting – which I believe is a non-final argument worthy of even being debated heatedly on the internet as if the netizens are barking up the wrong tree.

Sexy killer is a form of journalistic documentary produced by a team from WatchDoc production called “Advocative” journalism in which the visual product argues strongly and presenting a case as bold, as strongly as it possibly can to invite the audience for a call to action. It is in its nature that this advocative journalism should be presented in a very argumentative way, without it, the documentary will lose its fangs unable to bite into anyone’s consciousness or appeal to them in the slightest of sense. This is a mere classification of genre but not an evaluation whether this documentary is worth watching or whether its arguments are true / false. Asians are known to avoid debate and discussions it is written in our social system to prefer calmness, venturing beyond this will be regarded as going into a heated debate or a ‘fight’. This social structure is ingrained in what is named “High Power Distance Culture” by Geert Hofstede (1997, Cultures and Organization: Software of the Mind). Despite the availability of “Musyawarah Kekeluargaan” (family-mediated discussion) ideology, this discussion / debate is still controlled and approved by a senior figure to round arguments up, often not by worth of wisdom but by submission to the senior authoritative figure assumed to be wise.

In that sense, handling different opinions and often requiring settlement via a debate or dispute is not one of Asian culture’s trait. Paired with majority of Indonesians’ poor writing and idea organization skills (through practice of essay writing) detecting main argument of a documentary such as Sexy Killers become extremely difficult. In its most basic argument structure, the documentary opens itself by presenting us the lives all urbanites know, the glamorous city nights, a newly wedded couple, electrical equipment and utensils and the power outlets to which they are all connected to and continuously consumes energy. Just through this opening scene we can already sense that the main argument should be about energy consumption. Not the eroticism the newly wedded couple is trying to perform, nor trying to sell us electrical utensils if any of the latter is deemed to be the main narrative of the documentary one can then see the remainder of the documentary to see if their argument favors the conclusion. The rest of the documentary talks about how people are being treated unjustly, being confined and surrounded by huge corporations and the grievances the coal mines have caused them leading to the most sneered upon part of exposing the authorities and the policy makers behind the coal industries themselves which causes a lot of ruckus and disfavor being labeled as can of worms “chaos maker” because of the debate they sparked.

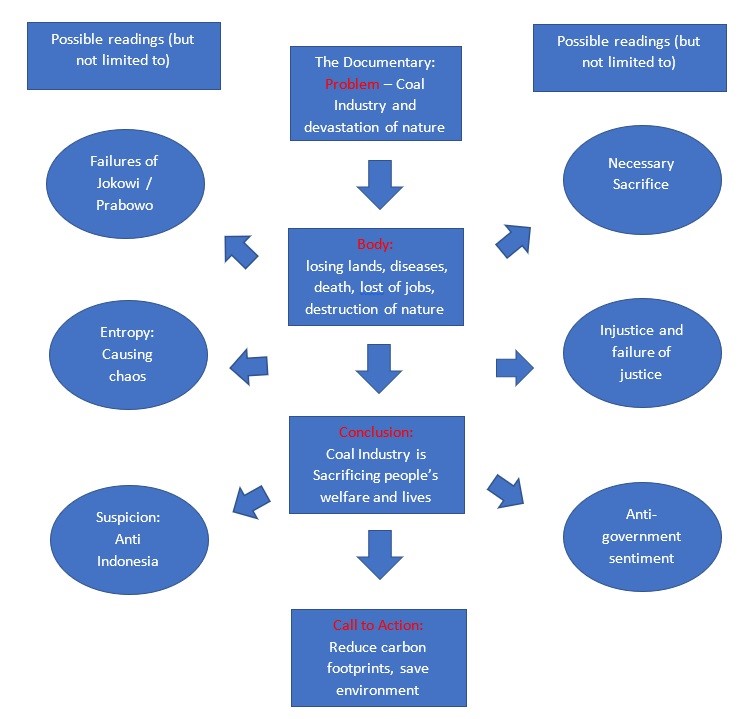

There are notably many responds over the internet at how people react to this documentary. The aim of this article is not to confine you to one or two concluding perspective, but to help us realize the freedom we all have to respond to this documentary. All the available perspective over the internet are mere spectacles made to fit specific groupings and if sorted will fall into some categories of pro – against dichotomy. What of those that genuinely am interested in saving the nature without ever considering the possible false truth and the sugar-coated notion of national progress? Are not those people worthy of being regarded as true humanist for wanting to preserve the welfare of our living? On an ideal level, this alone is the sole fuel that allows the documentary to exist regardless of all the other mis-projected and mis-interpreted perspectives available online. Below is an example how there are possible readings (which are not wrong and are acceptable) but they are completely outside of what the documentary is arguing about and are rather side impacts of the main issue but not the main issue concerned with coals.

An art Historian James Elkins notes that the more informed we are by all the outside voices (in his cases were labels, tours, catalogues) the more detached we become from experiencing the work of visual arts by our most private instincts, our opinions were hijacked beforehand disabling ourselves from thinking, feeling and assessing things objectively. From the modest model of possibilities above we can all see how far the charts in the left and right columns are from the main train of thoughts and context of the documentary. A lot of times, the functionality of that documentary becomes completely obscured, drenched in the loudness of sneering posts and mis-interpretations of issues not within the theme of the documentary. And by this, Elkins (2000, How to Use Your Eyes) laments just how much of a loss this contemporary culture has brought us: instant perspectives. Debates are actually good because of how much discussion it can bring if executed in civilized manner, sharpens logic and idea organization skill but the internet instant culture, the vain internet arguing leaves much to be desired for when it comes to furthering the maturity of re-negotiation and extracting results for the greater good far beyond useless bickering.

Comments :