Spaces of Amalfi

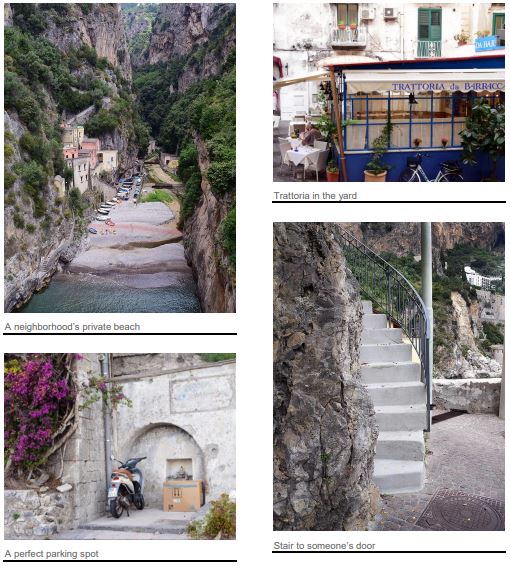

As enchanting as both Mediterranean Sea and Southern Italy’s landscape are, Amalfi is not about these, but what lays in between: its coast, the rough meetings of the two elements. The 50 kilometers of line on the edge of Sorrentine Peninsula is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, listed not only for its natural diversity, but also its built environmentsettlements that had been established as early as the Middle Ages. Every civilian’s desire to live as close as possible to the sea, supported by the extreme contour of the land, created a settlement typology that is peculiar. The towns along Amalfi Coast are made out of vertical levelings- the rarely considered Z-axis in the planar- to accomodate the brutal, wishful notion. However selfish that might sound, the end product is suprisingly very communal.

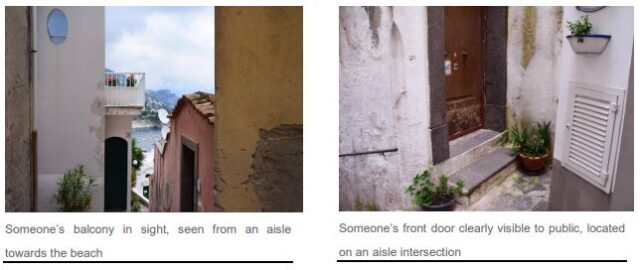

The answer of how such utopic idea is achieved is simple: people of Amalfi sacrifice a slice of their privacy in order to live on top of one another. Here we are talking about shared semi-public spaces: your front porches functioned as alleyways, your rooftops as viewing galleries, your yards as plazas. As long as it is not behind your door, it should be accessible to anyone. A scary concept. But this ambiguity of space generates a sense of transparency that is very much enjoyed by both locals and visitors.

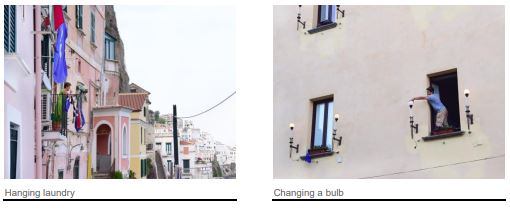

My visit to Amalfi was filled with getting lost in small aisles to find my way down to the nearest beach- and by ‘aisles’, yes, I mean someone’s front porches. I remember observing locals coming home from groceries shopping, hanging laundry on their balconies, or simply standing smoking right at their doors. However, the most intimate moment happened when I walked pass by a kitchen while the owner was cooking. The mere second that we exchanged smile; he added a bonus in the trade: the smell of homemade Italian sauce. My thought on Amalfi’s spatial transparency then expanded; the shared semi-public spaces do not only arouse visual experience, but also audial and olfactory. At night, I could tell my neighbors were conducting dinner by hearing the sound of cutleries clicking from my room; in the morning, I could tell when they were leaving for work from the door’s slam. I felt as if I was in sync with the rhythm of the town.

Comments :